At an amusement park in Bergen in 1928, a 69-year-old woman walks over to the shooting gallery. Some young boys shout “old hag” as she passes by. The woman picks up the gun and shoots at the target. She keeps shooting until she wins all of the first prizes. The woman is the sculptor Ambrosia Tønnesen, and it is not the first time she has defied society’s expectations of her.

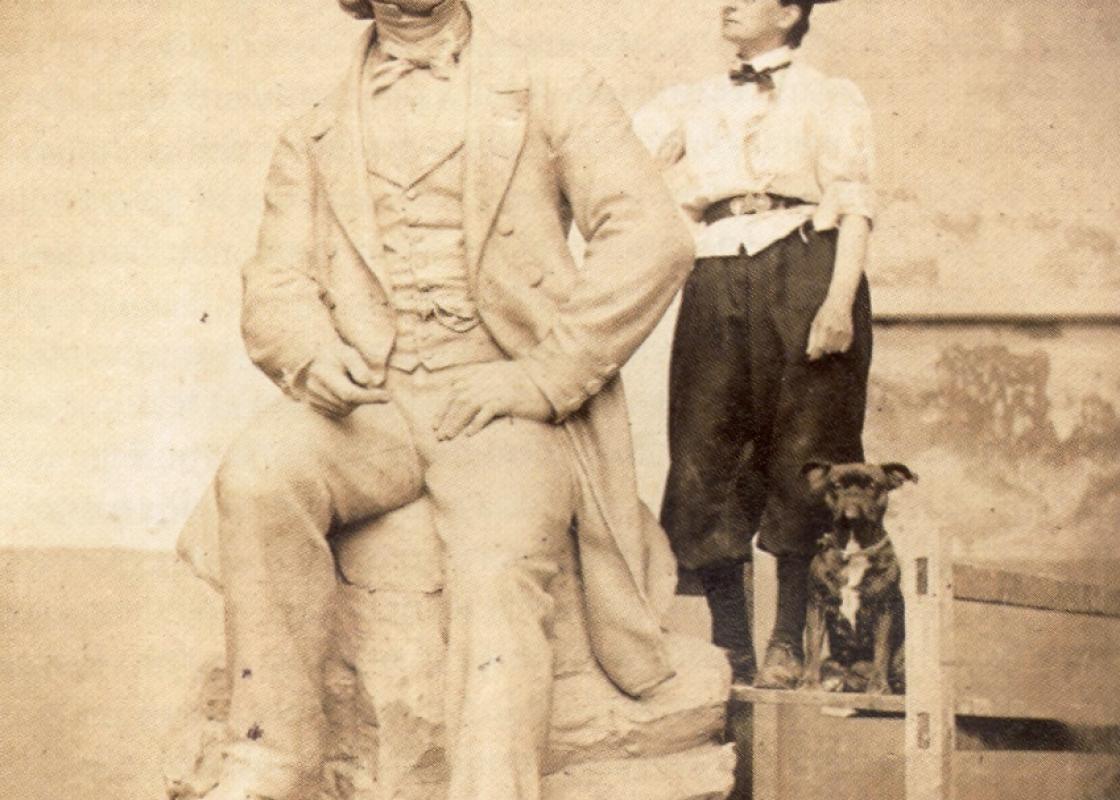

“There is a great deal of evidence that Ambrosia was a tomboy when she was growing up and that as an adult she did a lot of fishing, pistol shooting and other outdoor activities. As a sculptor, she was interested in all things physical. She herself loved to chisel the marble,” explains Jorunn Veiteberg, who recently published the biography entitled Ambrosia Tønnesen: «Stenhugger i det Fine» (“Ambrosia Tønnesen: The marble stone cutter”).

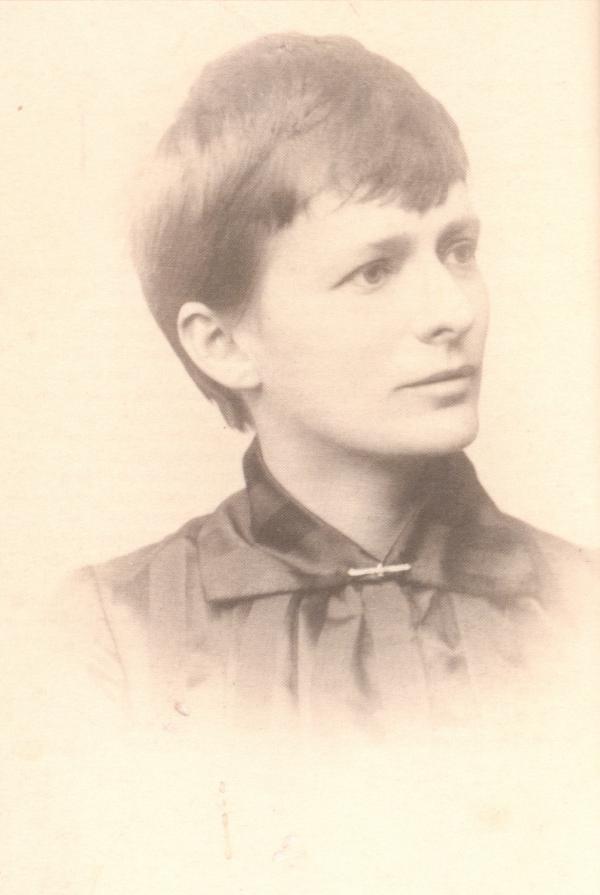

Ambrosia was born in 1859, and she lost her father when she was only nine years old, which put her family in dire economic straits. So as not to be a burden to her siblings, Ambrosia had to either earn a living or get married. The second option was the most common. Ambrosia was engaged to be married at a young age, but she broke off the engagement right before the wedding was to take place.

“Women from the bourgeoisie had few career choices. Many became artists because girls were raised to take part in aesthetic activities,” explains Veiteberg. The painting profession was also open to all and could easily be done at home.

Her talent was discovered

Ambrosia got her first job as a teacher, and she took courses in drawing at a technical vocational school on the side. Public art education did not exist in Norway, and the school was for young men studying to be artisans. Women were permitted to attend if there was space available.

It was common to take courses in modelling in addition to drawing, and thus it was discovered that Ambrosia had a special talent.

Sculpture was thought to be unsuitable for women; it was hard, dirty work, and it required having a studio outside the home,” says Veiteberg.

Ambitious and professional

There were art schools abroad, but the public ones were only for men. Women could take lessons from private teachers, but they often had to pay much higher prices than men. Ambrosia studied first in Berlin and later in Paris.

“From what I can see, Ambrosia was fortunate to have received a lot of free training, probably because she was so good. Moreover, all the attestations she received from her teachers stress that she was strong willed and hardworking. She focused on being highly professional,” explains Veiteberg.

In the few sources that the art historian has of Ambrosia speaking about herself, which are mostly interviews, she never talks about art as a romantic calling but as hard work – albeit work that she loved. Sculptors, more so than other artists, depended on commissions to execute their pieces. Marble is expensive, and it was common practice to present a rough cast in plaster in the hope that a patron would commission the piece in marble.

“Ambrosia got many commissions. Norway was in the process of becoming an independent nation, and this created a demand for statues of heroic figures. This may not have been the most exciting type of work she could have, but it gave her a good income,” says Veiteberg.

Ambrosia lived in Paris for over 20 years, and along with one of her first teachers, Stephan Sinding, she was probably the Norwegian sculptor who had the most international commissions.

Not a life of self-denial

Jorunn Veiteberg believes that Ambrosia was respected as an artist on equal footing with her male competitors, but she did not achieve this standing without effort.

“Like other successful female artists, Ambrosia was good at balancing. She stayed away from associations that were exclusively for female artists, probably because they did not distinguish between amateurs and professionals. She wanted to compete on the same terms as men, even though she understood that gender played a role,” says Veiteberg. Critiques of her artwork often said that it was very good, considering it had been made by a woman. She did not receive many grants, but this did not necessarily have anything to do with gender. It may have been that she did not have many supporters in Oslo, the seat of power, as she lived in Bergen when she was in Norway.

“But she got large commissions, and she got them early compared with other sculptors. And she received a lot of attention,” Veiteberg points out. Ambrosia also received a great deal of support from her family. They did not oppose her travels abroad, as many female artists experienced, and they were clearly proud of her.

Veiteberg finds that it is more interesting to look at what was possible for a woman to achieve rather than what the ideology of contemporary society said they should do.

“Several opportunities arose for women at this time. It is interesting to see how Ambrosia negotiated with society to create the life she wanted for herself. And all the evidence suggests that she got it,” says the art historian.

The exception that affirmed the natural woman

“To be sure, sculpting the head was the worst part because I nearly fell backwards several times. My skirt always got in the way, but after I started wearing my cycling bloomers, I was much more comfortable,”

said Ambrosia to the magazine Urd in 1902 about the process of creating the large sculpture of Norwegian painter J.C. Dahl.

Ambrosia cut her hair short long before most women did, and she both worked in and bicycled through Paris in cycling trousers that revealed her calves.

“This shows that there was not just one way for women to act. Ambrosia pushed the boundaries quite far, but she balanced this in a way that did not bring her many reprisals, other than from young boys who taunted her as she bicycled past,” says Veiteberg. By wearing masculine clothes, women avoided being taken for prostitutes, as single women on the street often were.

“Ambrosia went far in her personal life, but she did not make a mission of it, and consequently she did not threaten the social order. Instead she became the exception that affirmed how most women should live,” the art historian believes. In her art, Ambrosia followed the tastes of the bourgeoisie.

Nor did she give her public support to women’s issues as long as these were controversial. But after women gained access to education and the right to vote, she participated in the women’s rights organization where she was praised for her efforts. She was also one of the first to sculpt women who attracted attention in the public sphere, such as Amalie Skram and Gina Krog.

“She obviously identified strongly with these works,” says Veiteberg.

Ambrosia also took part in a competition to create the first memorial statue of a Norwegian woman – the author and feminist Camilla Collett. Ambrosia’s proposal showed Camilla as a lively, committed woman. She received third place for her proposal, but the commission was given to Gustav Vigeland, who was not part of the competition. Vigeland’s statue, which still stands in the Palace Park, shows an elderly, tired Camilla with her head bowed. Many of those nearest Camilla would rather have seen the commission go to Ambrosia, and a private patron ensured that she could sculpt a smaller version in marble.

Alone in work, but not in life

Her French colleagues referred to Ambrosia as the “woman who works alone” because she did not use assistants in her studio. It was unusual for sculptors to do all the heavy work themselves.

“She was not part of the artistic network either, and she is not mentioned in the memoirs of other artists. Women in art history are often remembered through their association with a man, as a lover, wife or model, but Ambrosia did not assume these roles,” explains Veiteberg.

However, Ambrosia had strong female friendships, and the most important of these was with Mary Banks from England. The two women lived together for over 30 years, until Mary’s death. They are buried in Bergen under the same gravestone.

“This friendship shows that art did not replace marriage for Ambrosia,” says the art historian.

She believes it is important to place emphasis on what researchers call “romantic friendship”, which was not uncommon.

“As an art historian, I am not used to writing much about my subjects’ private lives, but just as female artists have been rendered invisible, so have their same-gender friendships and lifestyles. For this reason I think it is vital to show that this way of living also has a history. Women who were registered in the statistics as unmarried and single could live in an intense relationship that entailed both practical and social support,” says Veiteberg.

She believes the term romantic friendship best describes this form of cohabitation and calls for caution in applying contemporary concepts to the past. Words such as “lesbian” and “homosexual” were not found in the Norwegian language at the time when Ambrosia and Mary met in 1888, and we cannot know whether they had a sexual relationship. But there is no doubt that “Mary was the best thing in her life”, as friends of Ambrosia wrote in a song for her.

Translated by Connie Stultz

Jorunn Veiteberg has a dr. philos. degree in art history and is a professor at the Bergen National Academy of the Arts with an affiliation to the curator studies and the theoretical component of textiles and ceramics. Veiteberg has been a member of Think Tank: A European Initiative for the Applied Arts since 2004.