Covid-19 is not the first pandemic in human history, nor will it be the last. But have pandemics affected women and men differently through the ages? And can we learn anything about why and how, which may help us understand more about what is going on today?

“Pandemics are a magnifying glass that sheds light on social conditions, gender included,” says May-Britt Ohman Nielsen, professor of history at University of Agder.

Case history into consideration

Nielsen’s fields of expertise are medical history, illness history, health history and history of epidemics. She emphasises how pandemics have affected women and men differently by using examples from cholera and tuberculosis.

“Infectious diseases affect women and men differently, primarily because women and men have different roles and function through history,” she says.

Tuberculosis is one example of a disease that has had different effects on the sexes through the ages, according to Nielsen.

“The disease is still active and widespread in large parts of the world, and it develops slowly. People live with the disease for a while. Gender and gender experiences are therefore often seen more through the case history than with sudden illness and illnesses that people only live with for a short period of time,” she explains.

“The disease spreads through droplet infection, and the source of infection is often difficult to trace precisely because it develops slowly. Infected persons may thus have been ill for a long time before the symptoms occur and the infected or their surroundings become aware of them.”

Men spread infection, women nursed

Men were often the first to be infected during pandemics such as cholera and tuberculosis because they travelled more, in professions such as sailors, tradesmen and soldiers, Nielsen explains.

“Consequently, men were also the ones to contribute most to the spread of diseases in larger circles, as they travelled, were infected and brought the disease home with them.”

At home, the infected men were often nursed by their sisters, mothers, wives and daughters, who then became infected as well.

“It was not unusual that the family’s women and other female relatives felt pressure to take care of the men regardless of whether they wanted to or not. Those who brought home the money took precedence in the family regardless of how dangerous the disease might have been,” says Nielsen.

“Traditionally, women have carried the burden of care and taken on the emotional responsibility, which make up the greatest difference between men and women with regard to illnesses and pandemics. We see this especially when it comes to children, spouses and parents.”

Read: How do gender perspectives in migration health look like?

Guilt and shame

In order to get infected with cholera, you have to swallow the bacteria. In other words, it infects through contact, but primarily through the drinking water. When the source of infection was not found as a result of direct contact, other theories about the spread of the disease took root, according to Nielsen. These theories were also gendered.

“For instance, many believed that cholera was a punishment from God. And there were different theories about why women and men were punished,” she says.

When it came to the men, they were often thought to be punished for drunkenness, whereas women were infected because they were promiscuously dressed and had bad morals

“When it came to the men, they were often thought to be punished for drunkenness, whereas women were infected because they were promiscuously dressed and had bad morals.”

The fact that tuberculosis could be connected to hygiene also affected men and women differently. For instance, tuberculosis brought along strict requirements for the housewife in terms of infection control measures and hygiene, Nielsen explains.

“If a family was infected, the woman of the house might be considered a bad housewife who failed to keep a clean home. Tuberculosis resulted in a lot of shame, and mobilised the women’s role in the home,” she says.

“The men were forbidden to spit, whereas the women were required to clean.”

Plagues and globalisation

Ole Georg Moseng, professor of history at University of South-Eastern Norway, has studied the history of plagues. He also draws parallels to today’s epidemic.

“Like covid-19, the plague spread through increased globalisation,” he says.

“The plague has been a part of human history since time immemorial. The oldest recorded case is from 3 900 BCE, and the last major epidemic is from 2017 in Madagascar. Plague outbreaks occur in several countries across the world every single year.”

In other words, the plague still affects us. But as a pandemic, we are primarily talking about three major waves, Moseng explains. The earliest recorded pandemic occurred in the early Middle Ages between c. 540 and 750 CE, the second began in 1346 and lasted until 1722, whereas the third pandemic wave occurred in the late 1800s.

“The first outbreak started in the cities that at the time made up the centre of civilisation: Rome, Carthage, Constantinople and in the vicinity of Alexandria,” says Moseng.

During the second and largest outbreak, which began in Crimea in 1346 and is referred to as the Black Death, the plague spread to large parts of Europe through travelling tradesmen and explorers. Repeated outbreaks in Western Europe occurred up until the early 1700s.

“We may, therefore, assume that those who largely contributed to the spread of the plague were men, particularly through their profession as tradesmen,” he says.

“The third plague pandemic broke out in India and China in the late nineteenth century and spread all over the world during the course of two decades. In Europe, it caused a number of minor outbreaks of plague around the year 1900.”

“Women most sorely affected”

Moseng explains that the plague bacteria is transmitted to humans via fleas from wild rodents. And during the Black Death it particularly spread through the black rat, which subsists on grain and grain products, but is more or less extinct in Europe today.

“We have relatively good data concerning gender differences in terms of how the plague affected people from the 1600s onwards, and it looks like women were most sorely affected by the plague,” says Moseng. But recent studies of the Black Death in the 1340s indicate that the same may have been the case back then.

The black rat may be one possible explanation to why more women than men seem to have been infected with the plague.

“Women stayed more inside the houses than men did. One can, therefore, imagine that they to a larger extent became victims of infections from the rats, which thrived in houses where they were close to humans,” he says.

The Black Death resulted in an enormous and persistent decline in the population in Europe, which led to poorer conditions for women in the long term

“In addition, women held traditional caring functions, which made them more exposed to infection. They had the main responsibility for the children and the elderly in the family, and their job was to care for those who were ill.”

Moseng states that another consequence of the plague that is more indirectly gendered is that it contributed to the collapse of the feudal system.

“The Black Death resulted in an enormous and persistent decline in the population in Europe, which led to poorer conditions for women in the long term,” he says.

The land rent went down and fewer people paid taxes. The feudal lords, that is, the big farmers, kings and the church, lost power. The workers’ wages went up, and the petty farmers had more money to spend.

“As a result, the land-owning aristocracy’s economic, political and social hegemony was weakened, which laid the foundation for the growth of the bourgeoisie. In bourgeois society, women had less power than in the agricultural feudal society,” says Moseng.

“Feudal society was hierarchical, but women were nevertheless more equal to men in their life as a housewife on a farm,” he says.

“The wife on the farm had a lot of power, whereas bourgeois norms ensured that the men were given a more distinct leader position within the family.”

Read: Major gender gap in health research

Slightly more men died of the Spanish flu

“The Spanish flu came to Norway in 1918, and led to the death of 15.000 Norwegians, or 0.6 per cent of the population. Approximately half of the Norwegian population were probably infected by the disease, according to Svenn-Erik Mamelund who is a demographer and pandemics researcher at Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet).

Mamelund explains that the flu pandemic affected Norway in four waves: One in summer and one in autumn 1918, one in winter 1919, and one ‘echo-wave’ in winter 1920. The first infected were discovered on Kristiania on 15 July 1918. Two out of three Spanish flu deaths occurred in autumn 1918, and in 1918, the number of deaths among the infected was twice as high in autumn than in summer.

“With regards to gender differences and international mortality rates, we do not have enough data to say anything general. But it is likely that a few more men than women died of the Spanish flu, as was the case in Norway. Furthermore, people around the age of thirty were affected particularly hard both in terms of sickliness and mortality,” he says.

“Especially during summer 1918, more men than women were infected. Many men were probably affected at that time because they had broader and more frequent contact with others through work and social activities than women in that period.”

Young adults particularly affected

The Spanish flu affected primarily young adults between the age of twenty and forty. That is also the age during which women are most fertile.

“This is part of the explanation to the dramatic decline in the birth rate in 1919, and nine months after the Spanish flu ravaged at its most intense during autumn 1918 in particular. Fewer children were conceived as many people resisted sex either because they feared being infected or because they were already ill. The mortality rate among pregnant women increased, especially during the late stages of pregnancy. The number of miscarriages also increased,” Mamelund explains.

“Furthermore, many men and women lost their spouse to the flu. Approximately 4.800 people were widowed in 1918–19, and the Marriage Act at the time required at least one year of mourning before one was allowed to re-marry. Unless a woman was already pregnant when she lost her husband to the Spanish flu, she was by law disallowed from conceiving a new child until after she had re-married. Of course some women did conceive outside of marriage, but this was not common.”

Mamelund therefore maintains that the subsequent baby boom in Norway in 1920 is a result of the Spanish flu rather than being connected to the end of the First World War as many historians have claimed.

“The 1920 baby boom is the greatest in Norway, only beaten by the one following the Second World War in 1946. It is probably because many people postponed marriage and childbirths until the epidemic was over in 1919. Besides, Norway did not participate in the First World War,” he says.

Here Mamelund draws parallels to the current pandemic and refers to a recent opinion piece in the Norwegian daily paper DN , which states that the fertility rate in Norway is in decline due to the corona epidemic.

“The fertility rate has been in decline for a long time in Norway, and the fact that young fertile people now find themselves in a society in lockdown may cause further decrease in the number of childbirths,” he says.

Widows were sorely affected

Coming back to the Spanish flu, Mamelund maintains that women who lost their husbands were probably affected harder than men who became widowers.

“At this time there was no such thing as widow’s pension and social security schemes, and the women moreover lost the family’s breadwinner,” he says.

“I would love to do more research on how it went with the bereaved during this pandemic. What coping strategies did they have? What happened to all the orphans? Did women apply different strategies than men? I believe they did.”

People wanted to leave the pandemic behind and move on

Mamelund refers to a story from the Trøndelag region in the Norwegian midlands, in which a woman was left behind with two small children when her husband and two other children died of the Spanish flu.

She did not re-marry; instead, she separated a parcel of an acre of land and sold the rest of the farm in 1919. She built a house on her part of the land and bought a cow, a goat and hens for the money she got from the sale. She also made her daughters work on farms during their holidays to ensure that they got enough and sufficiently nutritious food.

Resulted in widow’s pension

The Spanish flu also had consequences for women i terms of societal changes. In 1919, the Labour Party in Kristiania introduced social security benefits for single mothers and widows, Mamelund explains.

“This may have happened because they saw what consequences the Spanish flu had for women who lost their husbands to the disease and were left behind with small children.”

Many have referred to the Spanish flu as the forgotten pandemic, he says.

“But forgotten by whom? The doctors? Historians? The history of the Spanish flu is no victory narrative and it has no winners. I think that many people wanted to forget. They wanted to leave the pandemic behind and move on.”

Here, too, there are gender perspectives, according to Mamelund.

“Nancy Bristow, an American professor of history and pandemic researcher, has studied the Spanish flu by going through diaries, letters, photographs and other ethnographic and archive material. According to her, the doctors – who were primarily men – wanted to forget the Spanish flu altogether. They felt that they had lost the battle against the disease, and they felt powerless and disappointed.”

“For the nurses, however, it was the other way around. They felt useful during the pandemic, when they had cared for and comforted sick and dying patients. Even though there was no cure for the disease, nursing, food and care was still necessary and the nurses had been essential in this work.”

The idea of anti-bac is not new

According to Ole Georg Moseng at University of Oslo, there are some clear common features between previous pandemics and covid-19, for instance when it comes to the means we use to fight it.

“Isolation of the ill, lockdown, travel restrictions, embargo on trade, quarantines and use of facemask and tight clothing to prevent the spread of infection were also used to fight the plague in the 16th and 17th centuries,” he explains.

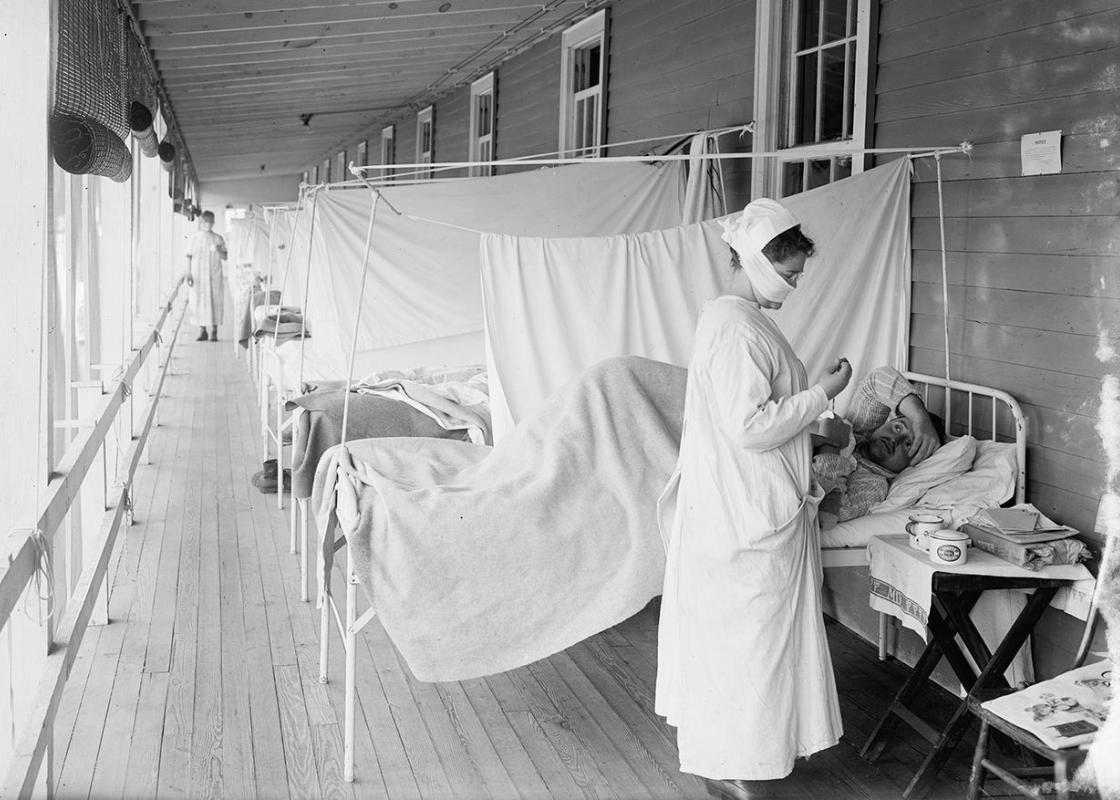

Especially the nurses, who were the ones who stayed most by the bedsides in the tuberculosis sanatoriums, were infected.

Moseng maintains that the idea of antibacterial hand gel is nothing new. In the beginning of the last century, 7000 people in Norway died from tuberculosis each year between the years 1890 and 1910. He says that the disease was fought without medicines, by the aid of hand wash, hygiene, social distance and public enlightenment.

“Here the nurses played an important role. They travelled around and educated people about the same things as the Institute of Public Health goes on about today: keep the distance, don’t drink of your neighbour’s cup and don’t ‘spit on the floor’.”

Read: “Women’s historical contributions are still ignored”

The Spanish flu as learning model

May-Britt Ohman Nielsen in University of Agder also sees several common features between tuberculosis and today’s corona pandemic.

“As we have seen several examples of today, public health workers are particularly exposed to infection. This was also the case for those who treated patients with tuberculosis,” she says.

“Especially the nurses, who were the ones who stayed most by the bedsides in the tuberculosis sanatoriums, were infected. And these were primarily women.”

But places in which there were mostly men were not free from infection either, according to Nielsen.

“In mines, boarding schools, the military, and not least in the front line during the First World War, diseases spread rapidly and resulted in a large number of men who were infected by tuberculosis and then the Spanish flu when it broke out in 1918.”

According to Nielsen, knowledge about previous pandemics provides us with invaluable information about how to handle today’s corona pandemic.

“The Spanish flu is the great learning model. Nearly everything we know about pandemic emergency preparedness and how the measures affect society long-term comes from this experience,” she says.

“How do isolation and closed down workplaces and schools affect relations between people? In addition, in what ways do these measures transform society and its long-term development? Here we may learn a lot from history.”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

- Epidemic: A disease that affects a large number of people within a community, population, or region.

- Pandemic: An epidemic that’s spread over multiple countries or continents.

- Endemisk: A disease that belongs to a particular people or country.