“Abortion is a universal female experience. In Norway, every one in three women have an abortion some time during their lives,” says Mona Holm.

Holm is curator and leader of the Women’s Museum Norway in Kongsvinger. The museum is located in a stately chalet from the 1850s. In June, the museum launched the exhibition HYSJ! (‘HUSH!’), which is intended to shed light on women’s experiences with abortion. It also places abortion within a historical, political and medical perspective.

The exhibition is among the Women’s Museum’s contributions to the project ‘Nå begynner ‘a med det der igjen’ (‘There she goes again’), about gender representation in Norwegian museums’ collections and exhibition practices (see fact box).

“Women will always have abortions”

"One, explicit premise lies at the foundation of the exhibition: Women have always had abortions, and they always will", says Holm.

“It is therefore important to work for safe abortions for women all over the world. We hope that this exhibition will help more women dare to speak about this topic, which is still stigmatising.”

Today we have both contraception and the necessary knowledge on how to avoid getting pregnant if we don’t want to. Yet it still happens.

Holm believes that to some women it might even be more shameful to have an abortion today than it was in the past.

“Today we have both contraception and the necessary knowledge on how to avoid getting pregnant if we don’t want to. Yet it still happens,” she says.

“Consequently, many women find it shameful: I should have known better, and still this happened. But we cannot plan everything in life.”

Read also: The nuclear family has become a political tug-of-war in Russia and Poland

An immaterial topic

Holm is leading us downstairs to the basement where the exhibition is located. Already as we enter the staircase, we encounter the strong colours of orange and pink, brown and peach. We see patterns of eye-catching motives in the wallpaper covering the walls: spirals, pessaries, condoms, birth-control pills, syringes and sperm cells.

The design of the exhibition is created by a feminist group of artists from Arvika in Sweden called OTALT.

“We chose to work with artists because it is easier for them to interpret the material in a way that makes it more accessible to the general public,” says Holm.

“They can highlight and interpret facts and multiple meanings. Abortion is an immaterial topic to which there are few physically related objects, particularly because we did not want to display any horror images.”

We have reached the bottom of the staircase and are standing in front of a wall covered with faces. Hundreds of women’s faces have been drawn in black against a white background.

“This represents all the women who have contributed to the exhibition with their personal stories about abortion,” Holm explains.

“Here, we are going to get a map with buttons on it. When you push a button anywhere on the map, it will illuminate the face of the woman from this area who has told her story.

For the youth

The exhibition’s most important target group is youth, according Holm.

“We want young people to identify with the exhibition, and we therefore invited a group of teenagers from a school here in Kongsvinger to give us feedback during the preparations,” she says.

“They were clear in their recommendation that the historical perspective should not be the first thing people encounter when they visit the exhibition. They wanted the first impression to be personal, something with which they could identify.”

Working with an exhibition without being able to meet the people you collaborate with has not been easy.

The exhibition consists of four rooms; one with individual narratives from women who have had abortions, one with stories from representatives from the health care services, one about activism and politics, and one displaying historical and philosophical currents.

“We have also created a timeline displaying the most important events in the history of abortion. But this timeline is placed along the ceiling to prevent it from disturbing the overall experience. Those interested in such facts therefore have to look up in order to read what it says,” Holm explains.

In the room with personal stories, there are two gold-plated desks with tilting mirrors. The mirrors show films of young women talking. You need to put on a set of earphones to listen.

“These are actors reading the women’s stories,” says Holm.

Much resistance

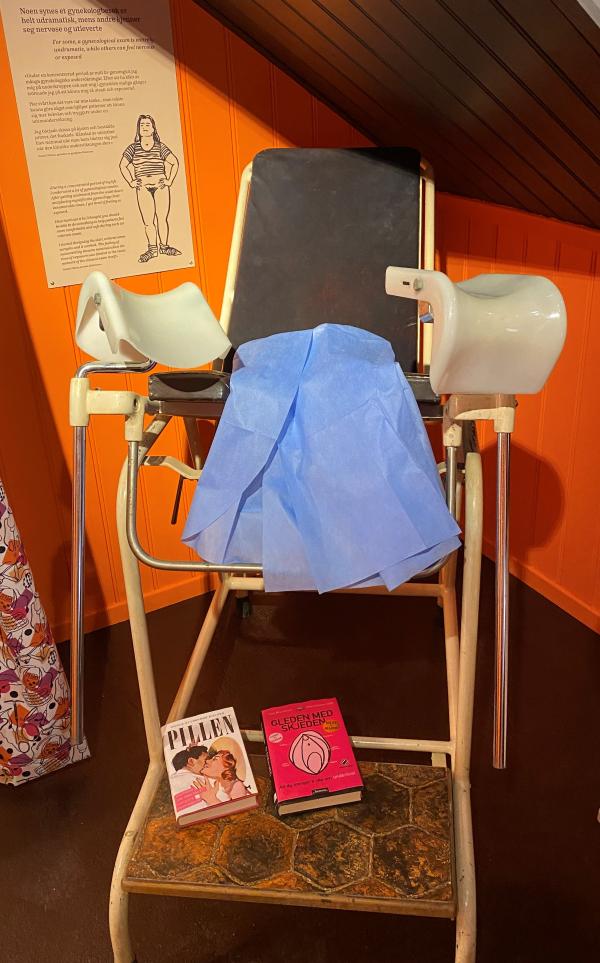

In the next room, we find ‘the midwife’s desk’. On the desk, there is a computer also showing a film with a woman talking. In this film, a midwife and a doctor are telling about their experiences of encounters with women who are having abortions. A gynaecologist chair is placed in the corner of the room.

“Health personnel’s narratives about abortion provide an important perspective that is vital to include in the exhibition. They are the ones with the best overview of the field, they know the relevant laws and regulations, and they can contribute by influencing the health care services that the women encounter,” says Holm.

The women who have contributed with their experiences of abortion have been recruited through the exhibition’s reference group. The group consists of representatives from Sex og Politikk (Sex and Politics), Sex og samfunn (Sex and society) and Amathea, nurses, a midwife, a doctor and OTALT, the previously mentioned partners in Sweden.

Holm explains that finding stories has been a difficult job. And the pandemic did not make things any easier.

“Working with an exhibition without being able to meet the people you collaborate with has not been easy. It has created a few barriers,” she says.

Still shameful

“Yes, abortion is still shameful,” says Gunhild Maria Hugdal.

Hugdal recently defended her PhD thesis at MF Norwegian School of Theology, Religion and Society. She has studied the stories of women who have made the choice either to have an abortion or to go through with the pregnancy.

The shame is there, in some contexts more than in others, of course.

“There is a long way from what is statistically ‘normal’ to what is ‘ideal’, the latter being the planned pregnancy during which everything runs smoothly,” she says.

“You can compare it with divorce. It is a widespread phenomenon that is largely normalised, but it does not represent the ideal. No young people would say, ‘When I grow up, I want to be twice divorced and have one abortion’. Nevertheless, approximately fifty per cent of us go through a divorce and every one in four women go through an abortion.”

Ethical dilemma

As an ethicist, she also interprets the shame in light of the traditional dilemma approach to abortion. In other words, the fact that abortion can be a difficult choice.

“Given that abortion is constituted as an ethical dilemma, it demands a certain type of justification. You therefore find yourself ‘on the minus side’ already at the point of departure,” she says.

“When something is constituted as a dilemma, the solution will never be recognised as ethically good, although both an abortion and a divorce may in certain cases be just that.”

The dilemma approach makes the phenomena more rigid, the dilemmas are non-negotiable and all our ethical attention is drawn towards the inextricable, according to Hugdal.

“The fact that something is constituted as an ethical dilemma represents, in itself, a sort of cultural taboo and social control, according to some voices.”

Whether abortion is connected to more or less shame today than in earlier times is difficult to say; it would require a comparative study, according to Hugdal.

The woman’s shame

“In many respects, I believe that abortion is less tabooed than it used to be, but I am not entirely sure,” she says.

“The shame is there, in some contexts more than in others, of course. This is also a type of shame that is largely placed upon the woman alone, and not on the man, since birth control is constituted as the woman’s responsibility. It is up to the woman to use birth control pills, a spiral or an implant, and thus it also becomes her responsibility and her ‘mistake’ if the contraception fails.”

Many women felt that sitting in front of a committee who were to decide whether you were allowed to have an abortion or not was degrading, and they could feel both shame and anger as a result.

On this particular area, research shows that young men today do not consider it their own responsibility if the woman gets pregnant. In this way, the abortion and the pregnancy are constituted at ‘the woman’s’, Hugdal explains.

“Additionally, it can be shameful to complete unplanned pregnancies in some circumstances. In previous times, one could hear that a man who made a woman pregnant by mistake had ‘ruined her life’,” she says.

“My research demonstrates that today, this accusation is directed at women who decide to complete their pregnancy despite the future father’s wishes. They risk being accused of ‘ruining the life’ of the father. The ideal for reproduction in our time is still narrow and constricted: when both the man and the woman work full-time they should have two children when everything else is in place.”

Anger and shame

Kari Tove Elvbakken, professor of political science at the University of Bergen and author behind the book Abortens politiske historie (‘The political history of abortion’), is uncertain whether women commonly feel shame when they choose abortion today.

“But given good access to information about how pregnancies can be avoided and to all types of contraception, unwanted pregnancies may easily be perceived as one’s own fault,” she says.

“Politics have emphasised the prevention of unplanned and unwanted pregnancies – the idea is that unwanted pregnancies end up in abortions. But the right to plan for things can also become almost like a duty.”

Whether the sense of guilt results in shame is an open question, and this will possibly vary from woman to woman, according to Elvbakken.

“Experiences from the time before abortion was legalised primarily give evidence of fear and anger related to being forced to go through illegal abortions,” she says.

“Fear because the women did something illegal, and anger because some women had to risk their lives due to social injustice, whereas those with resources and contacts could arrange to have safe abortions. It is not unlikely that many women kept quiet about illegal abortions not because of shame, but because they feared being punished.”

In the 1930s, the desire for legal abortion was driven forth by the fact that most of the women who had abortions were living under poor circumstances that made it impossible for them to have children. This changed in the 1960s, when an abortion committee were to decide.

“Many women felt that sitting in front of a committee who were to decide whether you were allowed to have an abortion or not was degrading, and they could feel both shame and anger as a result,” Elvbakken explains.

“The abortion activists’ driving force in the 1970s was the woman’s right to make decisions related to her own reproduction.”

Some stories are missing

The Women’s Museum in Kongsvinger has emphasised a wide representation of age, situation and geography in the stories chosen for the exhibition. They have received stories from all over the world through the international network for women’s museums.

“We wanted to display several perspectives on abortion; there is no key answer to this phenomenon. But the women who want to share their personal stories have often had dramatic experiences,” says Holm.

“This does not give an entirely representative image of reality, since most abortions are undramatic and most women do not think of it as a very difficult choice. Few women experience after-effects, neither physical nor psychological.”

Some groups are not represented in the stories, however. Narratives from immigrant women and Sami women are not included in the exhibition.

“We have not succeeded in getting enough stories. But I hope that stories from these groups will come later, when people have seen the exhibition and how the material has been treated and protected,” says Holm.

“Nor has it been easy to get men to tell stories from their perspective as a partner or boyfriend, either. But we have received a few, which is good. And after all, women’s experiences and women’s bodies are at the centre of this exhibition.”

We climb the stairs and go outside for more pictures. Light green birch trees surround the house and the garden abounds with dandelions.

“Our goal with this exhibition is to create a space for talking about abortion and to show that having an abortion is normal,” says Holm.

Read also: “Women’s historical contributions are still ignored”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

This article is part of Kilden genderresearch.no’s contribution to the project ‘Nå begynner ‘a med det der igjen’ (‘There she goes again’) – about gender representation in Norwegian museums’ collections and exhibition practices. The aim is to change the museums’ practice and way of thinking about gender. The project is led by the Women’s Museum Norway and Anno Museum.

Kilden contributes to the project with a series of articles about gender perspectives in the museums’ activities and exhibitions. We will be writing about the exhibitions connected to the project and interview researchers with expertise on the various topics. The objective of the articles is to shed light on the connection between gender and museums.

The project is funded by the Arts Council Norway.