“Thank you for the time you bestowed upon me yesterday. Thank you for this little first leaf – Thank you for being you and for being willing to support my life and pain!” Camilla Wergeland wrote the above in a letter to Jonas Collett, with whom she was secretly engaged, on 1 April 1839.

Is the letter as literature and a source for authors and authorship on the way out? asks literature researcher Tone Selboe.

Selboe is professor of literature at the University of Oslo, and has written the book Kjærlighetsbrev (love letters), which was published in spring 2023. In the book, she looks at letters written by Camilla Collett (1813–1895), Amalie Skram (1846–1905), Karen Blixen (1885–1962) and Bodil Cappelen (1930–) to (and about) the men they loved.

Tone Selboe is professor of comparative literature at the University of Oslo. She published the book Kjærlighetsbrev in 2023, about the letters between Camilla Wergeland (later Collett) and Jonas Collett, Amalie Müller (later Skram) and Erik Skram, Karen Blixen and Thomas Dinesen, and Bodil Cappelen and Olav H. Hauge.

Christine Hamm is professor of Nordic literature at the University of Bergen. She has, among other things, written a book about Amalie Skram and recently reviewed Selboe’s book in the journal Norsk litteraturvitenskapelig tidsskrift.

Letters with literary value

“The background to the book is that the letter as a medium is changing and may even disappear altogether. Moreover, there has been little research on love letters to date, at least in the Norwegian context.

Selboe has also previously researched and written about Camilla Collett and Karen Blixen, but has not focused on their letters before.

“The reason I chose these letters is that they are fantastic literature in themselves. I was also already familiar with some of the authorships,” she explains.

“The love letters I have selected in the book were written by young women in the period between the 1830s and 1975. All of them have been edited and published in book form before.”

According to the professor of literature, letters both represent the here and now and are texts for eternity.

“They are like novels about the lives of the women and the men who wrote them. And although the letter writers aren’t conscious of the story as they write – they don’t know how it will end – some of them also refer to the letters as novels, she says.

“Take, for example, Camilla Collett or Wergeland as she was still called when she wrote love letters to Jonas Collett. She kept everything she wrote, both diaries and letters, obviously with a view to publishing them.”

Camilla Collett was determined to become a writer and as a young woman she practised by writing letters to her friend Emilie Diriks. Later in life, letter writing became a source of income for Collett, including writing travel letters from Europe for Norwegian newspapers and magazines.

“Amalie and Erik Skram probably also though that their letters could end up being published,” says Selboe.

“Since the letters are published in book form, we read them as literature, or as something between life and literature. Letters are an interesting medium characterised by both oral and written sources.”

A reflection on the times they lived in

It was also important for Selboe to choose letters that put the genre in a historical perspective.

“Physical desire is unmentionable for Camilla and Jonas Collett, but it is an important topic in the letters between Amalie and Erik Skram."

“Collett and Skram belong to two different historical eras. Collett wrote and lived in the age of romanticism, while Skram's writing belongs to realism,” says Selboe.

“It's interesting to see how much the letters change from Camilla Collett’s to Amalie Skram’s time. Despite the fact that they were born only a few decades apart, she points out.

This is demonstrated, for example, by how desire, body and sexuality are referred to in the letters, exemplified by these lines Amalie wrote to Erik: “Can you not tell by my letters how my blood beats in joy over you and the passion you have awakened in me. You are a fool who does not understand the secret of that marvel that has made me brand new, someone other than the cold sphinx I used to be.”

“Physical desire is unmentionable for Camilla and Jonas Collett, but it is an important topic in the letters between Amalie and Erik Skram."

This is just one of several examples of how the love letters reflect the time they were written in,” says Selboe.

“The questions the two women raise in their letters, about the role of women and marriage, reflect the debates that raged in their own time.

The most important topic in the letters between Amalie and Erik is perhaps jealousy.

“Erik has a girlfriend when they meet, which shocks Amalie and makes her extremely jealous. She also remained his mistress for a while after he met Amalie. He justifies this on the grounds that a man needed to satisfy his physical desire,” says Selboe.

“Amalie was traumatised by her first marriage to a much older man and therefore had a difficult relationship with sexuality when she met Erik."

Breaking norms

All the women in the book are unique, and break with gender roles in their own time, says Selboe.

“Karen Blixen’s and Bodil Cappelen's letters belong to another time, but they also differ from Collett and Skram's letters in form,” Selboe points out.

“Karen Blixen's letters are about her love for Denis Finch Hatton, a British big game hunter she meets while living in East Africa. But she doesn’t write to him, but about him, in letters to her brother. And the letters between Bodil Cappelen and Olav H. Hauge are special because they started writing to each other before they met.

Blixen explores contemporary views of marriage and the relationship between love and friendship in her letters,” says Selboe.

“She reflects on what happens to love when a marriage is so easily dissolved. For her, friendship was more important than erotic love.”

Blixen ran a large coffee farm in East Africa alone after she and her husband divorced.

“Although she was undoubtedly part of the colonial project in Africa during the early 20th century, she was unusual for her time. She had a strong bond to the people who worked for her and started, among other things, a school for the children on the farm.”

In the age of the telephone

The letters between Cappelen and Hauge bring us nearer the present. Cappelen writes to Hauge because she has read a collection of poems he has written, which marks the beginning of a four-year correspondence between them. In the 1970s, most people had a telephone, but not Olav H. Hauge, so they stuck to letter writing.

“The letters between Hauge and Cappelen are also interesting in that their love was a result of the letters and not the other way around.”

Cappelen and Hauge got to know each other through their letters, and it is clear that the writing in itself had value for both of them, says Selboe.

“Cappelen calls her letters an ‘epistolary novel', which shows that she was more open than he was, and links her letter writing to her own life story. Hauge, for his part, often relies on other poets when he has anything private to say.”

Intimate, but not private

All the letters in the book make up distinct stories and are good examples of the love letter genre, according to Selboe.

“The letters are spontaneous, but also have a literary flair. They are intimate and private, but at the same time they resemble other love poetry in the way they express emotions.”

Selboe refers to the French literary theorist Roland Barthes who has written about the language of love in letters and poetry.

“Barthes compares the literature of love and the love letter by highlighting key features that appear in both types of texts. For example, ‘the first meeting’, ‘the declaration of love’, longing and jealousy,” she says.

The characteristics of falling in love across people and eras is astonishingly similar, Selboe points out.

“The blushing, the sweating, the longing, the palpitations and the fact that they are attached to a ‘you’. Writing love letters is also about clarifying your own feelings, she elaborates.

“These are common features of all the letters in my book, too. They revolve around the difficulties of establishing a relationship, about living together. These are letters that deserve more attention. Some of them are just fantastic.”

A room of one's own

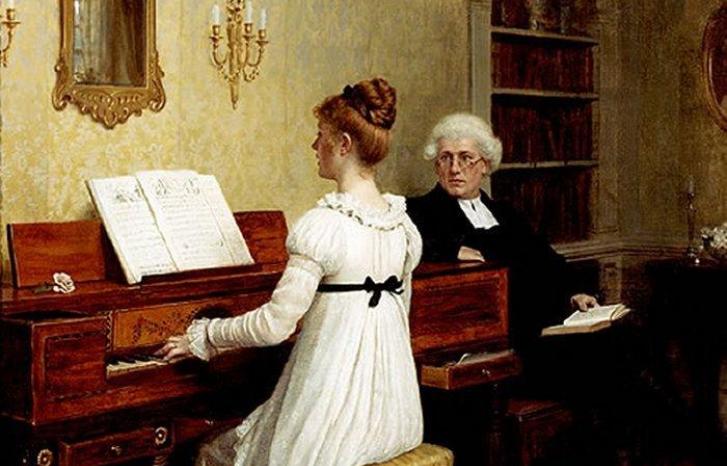

Selboe points out that the letter as a form of expression was particularly suitable for women, and makes reference to Camilla Collett, Amalie Skram and Karen Blixen belonging to a time when being a woman was associated with strong restrictions.

“The letter provided an opportunity for women to express themselves within a framework that was accepted. Writing letters was thus a place and a space where they could express themselves safely and freely about love, sexuality and friendship,” she says.

“This gives us, as readers of posterity, unique access to portraits of these artists as young women. Much of what they write about in their letters can be found in later literary works.”

Popular genre

“The letter was a popular genre in the 19th century. Everyone wrote letters, both men and women,” says Christine Hamm.

Hamm is professor of literature at the University of Bergen and recently reviewed Selboe’s book in the journal Norsk litteraturvitenskapelig tidsskrift.

“You could say that letter writing was more important for women because they had no other way to express themselves. Letters enabled them to put what they felt and thought into words,” she says.

“Writing letters therefore served as an awareness-raising process for many young women. Men had other arenas to express themselves in, while women, in line with the ideals of the time, were supposed to remain silent.”

It was taboo for women to raise their voices, while letters were a private arena, and therefore a place where they could express themselves freely and discuss things they could not write about in public, Hamm believes.

“The letters were also read aloud to family and friends, and were therefore only partly private. Skram, for example, made it clear in her letters to her husband what he could and could not share with others,” she says.

“The Skrams weren’t just anyone, either. We can therefore envisage Erik reading the letters from Amalie aloud to his author friends, thus making them part of the public debate.”

A slow form

My book is also a form of elegy, or memorial, to a medium that is in the process of disappearing, says Tone Selboe.

“Sweethearts write to each other today too. But it’s worth thinking about what will happen to today’s electronic exchanges. Will they be preserved for posterity? she asks.

“The time aspect in particular is different. The slow form. Although letters were delivered more often then than they are now, several times a day in large cities, most of the letter writers I write about lived far apart, so they had to be patient. The pace back then was very different to today’s electronic exchanges.