The Crafts Act of 1839 and the Trade Act of 1842 gave single women in Norway the opportunity to trade and provide for themselves for the first time. According to the so-called women’s article in the Crafts Act “feeble women above the age of 40 who are not able to provide for themselves in any other way” were given the right to produce their own goods. Following the Trade Act, they were also given a limited opportunity to trade. Previous to these acts, such rights had been reserved for men belonging to a certain rank.

There was a surplus of women in the cities. Between the years 1801 and 1835, the number of unmarried women rose by 42 per cent on a national basis. Whereas women from the lower classes worked and the peasant women were an important and integrated part of working life on the farm, the unmarried, idle bourgeoisie women could be an expensive burden both for the state and for their providing fathers.

"The new acts were made in order to protect the state and the fathers by giving unmarried and single women the opportunity to provide for themselves through crafts and trade," says historian Eirinn Larsen.

"This is an example of how measures which originally were made for other purposes have promoted gender equality."

Celebrating equality

The three scholars behind the book project “Norwegian history of equality 1814 - 2013” (Norsk Likestillingshistorie 1814 – 2013) are historian Eirinn Larsen, cultural historian Hilde Danielsen, and philosopher Ingeborg W. Owesen. This is the first and the only coherent representation of Norwegian history of equality thus far.

The history of equality is intertwined with the history of the Norwegian nation, and the scholars have been concerned with both national issues and equality, says Hilde Danielsen, who has been the project leader of the book.

"Our point of departure has been that equality is something which is constructed and created, and therefore difficult to define. The term equality may revolve around class, minorities, language and religion. Our focus is on gender, but we are constantly trying to show awareness of the term’s ambiguity."

Throughout the book, which covers 200 years of history, the term gender equality emphasises how women differ from men on the one side, and how women and men are alike on the other, and on both these aspects simultaneously.

See also: Feeling gender: from housewife to working mum

Uncultivated but free

The book starts with the Enlightenment. Ingeborg W. Owesen shows how the philosophical ideas concerning likeness and equality reached Norway from Europe. The cultural elite in Norway were highly cosmopolitan and actively participated in the import and export of thoughts and ideas.

An important promoter of the philosophy on equality from the Continent was the writer Ludvig Holberg. Owesen calls him the first Norwegian feminist. In 1745 he published a book on historical heroines, where he claims in his introduction that excluding women from important offices and activities is like prohibiting people with red hear from managing their own income, regardless of their financial insight.

The philosophical ideas from the Continent reached a society in which people at large were relatively egalitarian. Norway had no nobility and there were relatively small class distinctions, and this put Norway in a special position.

Following her visit to Norway in 1759, the British philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft claimed that Norway seemed to her to be the most liberal and egalitarian society she had ever encountered. The Norwegians were, according to her, uncultivated and little concerned with literature, but the press was free, one could express one’s opinion without fear of the government’s displeasure, and they seemed like the least suppressed people in Europe.

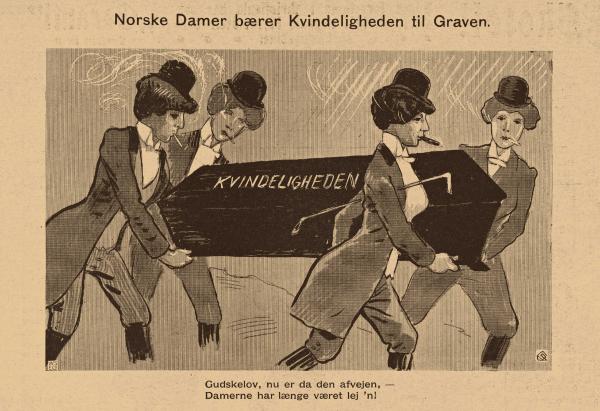

The feminists

Between 1880 and 1900 new women ideals developed and women started to take on new roles in public society. A few women were accepted to the University. Women wrote books and participated in the public debate. And they organised themselves in unions and associations.

Henrik Ibsen wrote A Doll’s House, Edvard Munch painted sensual women, Camilla Collett initiated a reader’s association for women, Aasta Hansteen wrote debate contributions in the papers and Gina Krog founded the Norwegian Women’s Association.

Like today, the feminists were not always unanimous. For instance, they did not agree on whether they should fight for immediate suffrage for all, or for a step by step introduction of suffrage. Some thought it would be enough to improve women’s financial situation. Krog was radical and wanted immediate suffrage for all women. This led to the division of Norwegian Women’s Association, and Krog founded new associations whenever she didn’t achieve majority for her view.

See also: Class more important than gender for school performance

Money and politics

The thought that all men should have the right to vote was scary enough. When universal suffrage for men was introduced in 1898, suffrage for women with a certain income level became an issue.

"The inclusion of men who contributed little to the Treasury was associated with dangers such as revolution, mass democracy and a state budget out of control," explains Larsen.

"The initial changes in suffrage in benefit of Norwegian women were made in order to reduce the effects of universal suffrage for men. Suffrage revolved around financial rights rather than the question of equal rights."

The fact that suffrage for women was modified according to women’s economy and class undermined the possibility of cooperation between women across classes and ranks. Working class women and the bourgeoisie suffragettes never really hit it off, neither in the 19th century nor after.

Party politics also played an important part. When the Liberal Party (Venstre) gained majority for their proposal concerning citizen rights for all men in 1898, the Conservative Party (Høyre), who had previously been opposed to suffrage for women, started to promote suffrage for wealthy women. They thought that these women would vote for the Conservative Party, and they were right.

"Women’s turnout in 1909 was very high," says Larsen.

"Actually, by voting far more conservatively than the men, their turnout was decisive for the election result."

The housewife and the provider

When suffrage for women was introduced in 1913, the major newspaper Aftenposten only mentioned the news in a short notice. The controversies were over long before the act was passed. The women’s associations were also reduced.

Due to the transformation from peasant to industrial society, the housewife and the provider became the new ideals for women and men. With this followed different roles and duties in society and unequal pay for equal work. The welfare state was founded on an understanding that the sexes were different but equal.

Both the labour party and the trade union had a conservative effect on the perception of gender roles in society. The child benefit reforms presupposed stay at home mothers, and the marriage act of 1927 facilitated for housewives who were provided for by their husbands.

"The ideologically motivated model which became the norm in the interwar and postwar period is a difference model, where men and women are supposed to have complementary roles and duties in society, though with unequal pay and with the heterosexual nuclear family as the norm," says Danielsen.

Simultaneously, employment outside the home became increasingly important for women, and both the education revolution and contraception was about to make its way.

Rebellion

"We were ahead in terms of suffrage for women, but apart from that Norway hasn’t got much to show for," claims Hilde Danielsen.

"The rebellion in the 70s came for a reason," she says.

Katti Anker Møller promoted legal abortion as early as in 1913, but the feminist movement didn’t win the battle until 1978. The equality act was passed the same year.

"We’ve called this disruptive period in Norwegian history «the long 70s» since it includes changes which were initiated in the 60s and consolidated in the 80s," says Danielsen.

"In the period between 1960 and 1990 women start taking university degrees and participate in the workforce – this time as the employees of the welfare state. This led to women’s increased participation in politics and to Gro Harlem Brundtland’s women’s government in 1986."

The equality country

According to Danielsen, the appointment of Brundtland’s government, consisting of ten men and eight women was the first occasion in which Norway appeared as gender equal to the world outside since the introduction of universal suffrage in 1913.

The last chapter of the book examines the period from the 90s till today and discusses how the term equality has come to include not only gender but also sexual, ethnical and religious minorities. It also looks at how equality has become a Norwegian value with which the nation measures and compares others against.

The authors emphasise that one of the biggest challenges in the years to come is the perception that Norway is the world champion when it comes to equality.

First version

This could easily have been a multi volume work. More research could also have been carried out, especially on minorities, men and masculinity, says Larsen and Danielsen.

"We wish there was more research on these aspects to build on," says Danielsen.

"This is a real problem not only for Norwegian gender research, but for Norwegian history of equality as well," adds Larsen.

The authors encourage others to write other accounts of Norwegian equality history. The first history of equality has been written, but it by no means wishes to stand alone.

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro

Hilde Danielsen is a researcher II in cultural history at the Uni Rokkan Centre in Bergen.

Eirinn Larsen is a post doctoral fellow in history at BI Norwegian Business School.

Ingeborg W. Owesen is a post doctoral fellow in philosophy at Centre for Gender Research, University of Oslo.