KILDEN Information and Documentation Centre for Women and Gender Research in Norway was launched in March 1999. Originally, it consisted of an online news magazine, a database on women and gender researchers, the scientific journal Kvinneforskning (Journal of Gender Research), and the photo collection Alma Maters døtre - kvinner på universitetet 1882-1982 (“Daughters of Alma Mater – women in the university 1882-1982”).

This is the story about the extensive work leading to the establishment of Kilden, and about how a Norwegian information and documentation service in this field came about.

The work leading to the establishment of what eventually came to be known as Kilden can be traced as far back as 1970, and many different actors have been involved along the way.

Moreover, Kilden is also part of the international women’s movement’s long traditions regarding information and documentation services.

A response to invisibility

The first services of this kind came about in the beginning of the twentieth century, when it became increasingly important to be able to present tangible documentation in order to legitimise the existence of women’s organisations and justify their demands.

Documentation centres also became an offensive response to the invisibility and distortion of knowledge on women’s lives and history.

With the growth of women’s research in the 1960s and 70s, the demand for these types of services increased. During the same period, they also became important for the authorities who were responsible for the development and implementation of gender equality politics.

The first women’s libraries

In a European context, we can distinguish between generations and types of documentation and information centres.

The first generation comprise women’s libraries and archives established as early as in the 1920s and 30s. The Women’s Library @ LSE (previously The Fawcett Library) was established as the first of its kind in London in 1926.

The collections grew rapidly thanks to book collections, photographs, pamphlets, money, and work force from activists from the women suffrage and feminist movement who were still alive at the time.

The first of its kind in France, Bibliotheque Marguerite-Durand, was established in Paris in 1932, and was based on the feminist Durand’s collection on the French feminist history in the Paris region.

The Dutch Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (today: Atria) in Amsterdam was established in 1935 due to concerns about the further fate of the feminist movement after they achieved suffrage and its motto was ‘no documents, no history’.

Information and documentation centres from this period have later been taken over by the authorities and are now characterised by large collections and abundant archives.

The second generation

The second generation of information and documentation centres arose in the 1960s and 70s, and consists of two different types of centres:

The first type is rooted in the growth and radicalisation of the feminist movement, the other is connected to the development and institutionalisation of the equality policy.

For instance, the independent feminist movement was the source of origin for The Feminist Library in London (1975), the Donnawomanfemme Library in Rome (1978), the FrauenMediaTurm in Cologne (1984), and approximately twenty other specialised centres in the Netherlands only.

Many of these centres are still mainly organised on a voluntary basis; due to scarce resources, the possibilities for professional management are limited.

Their documentation activity is often limited to cover explicitly feminist material, and several centres only give access to women.

The other type of information and documentation centres were initiated by the public authorities, and were more professionally run from the beginning.

Commission for the Condition of Women in Lisboa (1975), The Equal Opportunities Commission in Manchester (1977), and The Ministry for Women’s Rights in Paris (1982) are some examples of this type of centres.

Digitalisation in the 1990s

During the 1990s, a third generation of information and documentation centres began to take form. These were partly rooted in the feminist movement, in the women's and gender research communities, and within public equality politics.

This generation was characterised by international collaboration and new technology, as well as a certain connection between the needs of the women's and gender researchers and the needs of the equality politics.

It consists partly of already existing services that to a certain degree become modernised and web based, and partly of new services which are shaped according to new information technology. This is where Kilden belongs.

Other examples are the Nordic collaboration Nordic Information on Gender, NIKK, the Dutch International Information Center and Archives for the Women’s Movement, and the database Mapping the World, that contains details on approximately 400 information and documentation centres all over the world.

Sweden first in the North

The establishment of information and documentation centres in the Nordic countries have followed a somewhat different pattern. On the one hand, the Nordic countries were relatively late.

On the other hand, they established services that were well integrated in both the national library networks and in the women’s research communities already from the beginning (Larsen and Wedborn 1993).

The feminist movement has played a vital role as the driving force behind the information and documentation work in the Nordic countries as well.

Sweden came first with their Kvinnohistoriskt Arkiv (Women’s History Archive), established in Gothenburg in 1958. Due to the collaboration between the university librarians Rosa Malmström and Asta Ekenvall, and the Fredrika-Bremer-Association, the archive was located in the Gothenburg University Library.

The archive was organised as a foundation, and was run on a voluntary basis the first seven or eight years (Colbiørnsen 1972). In 1971, the archive was reorganised as a special collection in the University Library, called Women's History Collections.

Since 1997, Gothenburg University Library has held the national responsibility for women’s, men’s, and gender research.

A card index with references to women’s literature was terminated in 1992 and replaced with the database KVINNSAM. Here, the literary references were given keywords as they were indexed, and KVINNSAM’s subject database also became part of the Swedish university libraries’ common search system.

Women's History Collections publish a quarterly bibliography, Ny litteratur om kvinnor (“New Literature on Women”), and update their web pages continuously.

The collections register and make accessible archive material on individual women and women’s organisations in Sweden, including handwriting collections and newspaper archives.

See also: The history of Norwegian equality

The Danes follow

Denmark followed in 1964, when the Danish Kvindesagsforeningen (Feminist Association) paid for the establishment of Kvindehistorisk Samling (Women’s History Collection), which was linked to the State Library in Århus (Larsen and Wedborn 1993, Berg 1985).

The collections include material from a number of Danish feminist organisations, archives from individual donors, news archives, posters and photo/slide collections. From 1987, the collection gained status as a national women’s archive and was integrated in the State Library as a special collection.

The activity in Århus inspired Nynne Koch at Det Kongelige Bibliotek (The Royal Library) in Copenhagen to establish a so-called documentation service at the library in 1965. It was given the name KVINFO, Center for information om kvinde- og kønsforskning (Centre for Information on Women and Gender Research).

In 1979, KVINFO became an independent section under the Royal Library, but it moved into its own premises in 1982 and established an independent book collection financed by lottery funds. From 1987, KVINFO has been an independent foundation financed by the Ministry of Culture.

KVINFO functions as a national information and documentation centre. It publishes KVINFO’s web magazine, and operates various expert databases. Additionally, KVINFO offers lecture series, mentor networks, debate meetings and cultural events.

Information on equality in Finland and on Iceland

In Finland, the first information and documentation centre was established as an integrated part of the Department of Women’s Research at Åbo Academy in 1986, which also includes women’s history collections.

Later on, Minna – Centre for Gender Equality Information in Finland was established. Minna provides information on equality, research, and statistics, and keeps databases on research theses and experts. The centre is a sub-section under the National Institute for Health and Welfare, and is funded by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

On Iceland, Women’s History Archives at the National Library was institutionalised in the 1990s.

Additionally, Iceland has The Centre for Gender Equality, providing counselling and education in the field of gender equality for Icelandic authorities, non-governmental organisations, and businesses. The centre is funded by the Ministry of Welfare.

The Norwegian struggle

The effort to establish an information and documentation centre in Norway goes all the way back to 1970. In Norway, too, the feminist movement and female librarians played an important part in the development.

The Norwegian Association for Women's Rights (NKF), which had their own archives confiscated by the Germans during the Second World War, took the initiative to secure women’s history material.

Inspired by the archival work in Sweden and Denmark, NKF established a council consisting of Elisabeth Colbiørnsen, Sofie Rogstad, and Kari Skjønsberg in order to examine the case further (Skjønsberg 1984).

In 1974, the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights initiated a conference in Gothenburg in order to discuss Nordic cooperation on the registration of women’s history material. With this, they also got a helping hand internationally.

The preparations for the celebrations of the UN’s International Women’s Year in 1975 led to increased public interest in women’s questions and provided better opportunities for funding.

NKF worked both in order to establish a documentation service for ongoing registration and documentation of relevant women’s literature, and for an archive service to register and secure important historical archives.

Sofie Rogstad at the Private Archive Commission applied to the Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (the present Research Council of Norway) for money to establish a women’s archive, while the Norwegian Association for Women's Rights applied to the Ministry for Church and Education for funding for registration and documentation.

Both initiatives were successful and awarded funding in 1974, but posterity has shown that the ongoing information and documentation work was more fruitful than the archival work.

The works commence

In 1974, Gro Hagemann, later Professor of Women’s History, was employed in a three-year project in order to trace and register archival and handwriting material on women’s issues (Skjønsberg 1984, Hagemann 1978).

This work resulted in a catalogue of private archives kept in the University Libraries, The National Archival Services of Norway, and The Norwegian Labour Movement Archives and Library among others. Their focus is feminist organisations and important women within the feminist movement.

Unfortunately, three years wasn’t enough to finish the registration, and the collection and registration of women’s history material has never been brought to completion. The work to register the material from the feminist movement of the 1970s has not yet started.

However, recent research have discussed and documented several aspects of the 1970s feminist movement, amongst others a major research project carried out at the University of Bergen (2007-2011) called Da det personlige ble politisk. Kvinnebevegelsen på 1970-tallet (“When Personal became Political. The Feminist Movement in the 1970s”), and the extensive EU project Gendered Citizenship in Multicultural Europe: The Impact of Contemporary Women’s Movements (FEMCIT).

When women's research gathered momentum in the 1970s, many researchers felt that they started from scratch. They lacked knowledge of already existing written material either because this was poorly documented or because existing literature was hard to come by.

Accessibility was a problem partly because the women’s literature was interdisciplinary, partly because it was omitted from the common literature search systems, and partly because it was published outside the normal publication channels.

Our library systems simply weren’t appropriate for the researchers, and it became necessary to establish an individual documentation service for relevant women’s material.

Enormous increase in demand

The demand for information increased rapidly, and Norwegian researchers and students made their own private lists of references that were copied and distributed. Soon, bibliographies were also produced.

For instance, Kari Skjønsberg produced a bibliography for the Women’s Year containing 200 recent Scandinavian book titles on feminism and women’s studies. Biblio-bibliographies also appeared, that is bibliographies of bibliographies.

Internationally there was also a strong interest in women’s issues, and updated bibliographies were published continuously from the beginning of the 1970s. “New Literature on Women from Gothenburg” (Ny litteratur om kvinnor fra Gøteborg, previously Kvinnohistorisk arkiv: Förteckning över nyutkommen litteratur (“Women’s Historical Archive: Overview of recently published literature”)) appeared as a quarterly journal in 1971, and both Women studies abstracts from the US and Resources for feminist research from Canada appeared in 1972.

In addition to these, the various disciplines’ own bibliographies were produced. In 1980, a list of approximately 500 different bibliographies on women’s issues in the English-speaking world was made available.

Bergen was a natural place for a documentation service, as the university possessed professional library expertise and interest, an academic community of researchers working on women’s history and women’s issues within the social sciences, and a radical gender equality profile.

The university was internationally renowned for its radical gender equality committee from 1973. In 1975, Inger Johnsen was hired to facilitate the documentation service (Johnsen 1977, 1983).

The Documentation Service for Women’s Literature in Bergen was only favoured with a fifty per cent position. It was made permanent in 1978, but it nevertheless proved to be insufficient. The field experienced enormous growth, and there was an urgent need for information and documentation.

The demand for a strengthening of the Documentation Service was therefore continuously emphasised among Norwegian women’s researchers. The field of Women’s research was institutionalised during the 1970s with the establishment of the Secretariat for Women and Research in 1977 as its most obvious expression.

The Secretariat was established at the Council for Social Science Research at Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities (NAVF) for a period of five years.

In 1982, the Secretariat for Women and Research was made permanent and interdisciplinary, subject to the Board of the Research Council.

Asked the Research Council to prioritise women’s archives

In 1975, the participants of the first interdisciplinary women’s research conference, Women’s Aspects in the Humanities, asked the Research Council to prioritise registration works and to expand the interdisciplinary documentation service for literature on women’s issues and make it permanent (The Council for Research in the Humanities, NAVF, 1976).

The following year the committee responsible for the first report on Norwegian women’s research within the social sciences did the same (Cf. the report Forskning om kvinner. En utredning om muligheter og behov for samfunnsvitenskapelig forskning om kvinners livsforhold og stilling i samfunnet).

The committee asked the Ministry for Church and Education to provide funding for the documentation service, and they asked the Research Council for earmarked funding for particular projects such as an update of the literary card index and categorisation of articles during the period of establishment.

The participants at the conference on women's research within the social sciences, which was organised by the newly established Secretariat for Women and Research in 1977, applied for funding for “a sort of stencil bank in order to facilitate for academics doing research on women to have an overview of all available material in the field at all times” (Gornitzka and Ravndal 1977).

Proposition fell on deaf ears

These propositions were met with no response, however. Thus the participants of the conference Women’s Perspectives in the Social Sciences in 1981 asked the Secretariat for Women and Research to appoint a committee for literature and archives.

Under the leadership of Aina Schiøtz, the Secretariat appointed a committee whose task it was to assess various measures for the filing, registration, and accessibility of women’s research within the social sciences.

The committee were to assess whether the filing and documentation of relevant women’s research literature would best benefit from being part of already existing institutions or whether the feminist movement needed their own archive.

The members of the committee were Mie Berg, Bodil Espedal, Inger Johnsen, Lise Kjølsrød, Elisabeth Koren, and Marit Sand. They submitted their report “Biblioteks- og arkivtjenester for kvinnefaglig materiale” (“Library and Archive Services for Women’s Material”) in 1982.

In order to coordinate and present women’s academic interests within libraries and archives, the committee proposed the establishment of a merger of users connected to the Secretariat for Women and Research.

This proposition was never realised, but that was not due to a lack of interest: ninety people showed up at an event arranged by Association of Norwegian Research Librarians in Oslo and the Secretariat for Women and Research in March 1982 where the documentation issues were discussed.

In order to provide those interested in women’s research with a practical guide to library, documentation, and archive services, the committee arranged for the production of the publication Litteratur og arkiver i kvinneforskning (“Literature and Archives in Women’s Research”) written by Mie Berg in collaboration with Lise Kjølsrød and Elisabeth Koren. This publication appeared in 1985 (Berg 1985).

This work illustrated how other Nordic and European countries had established large, modern information and documentation services in the field of women’s research.

The international collaboration on documentation and archive production was in full play, whereas in Norway the documentation service was out of date and with insufficient funding.

The documentation work begins

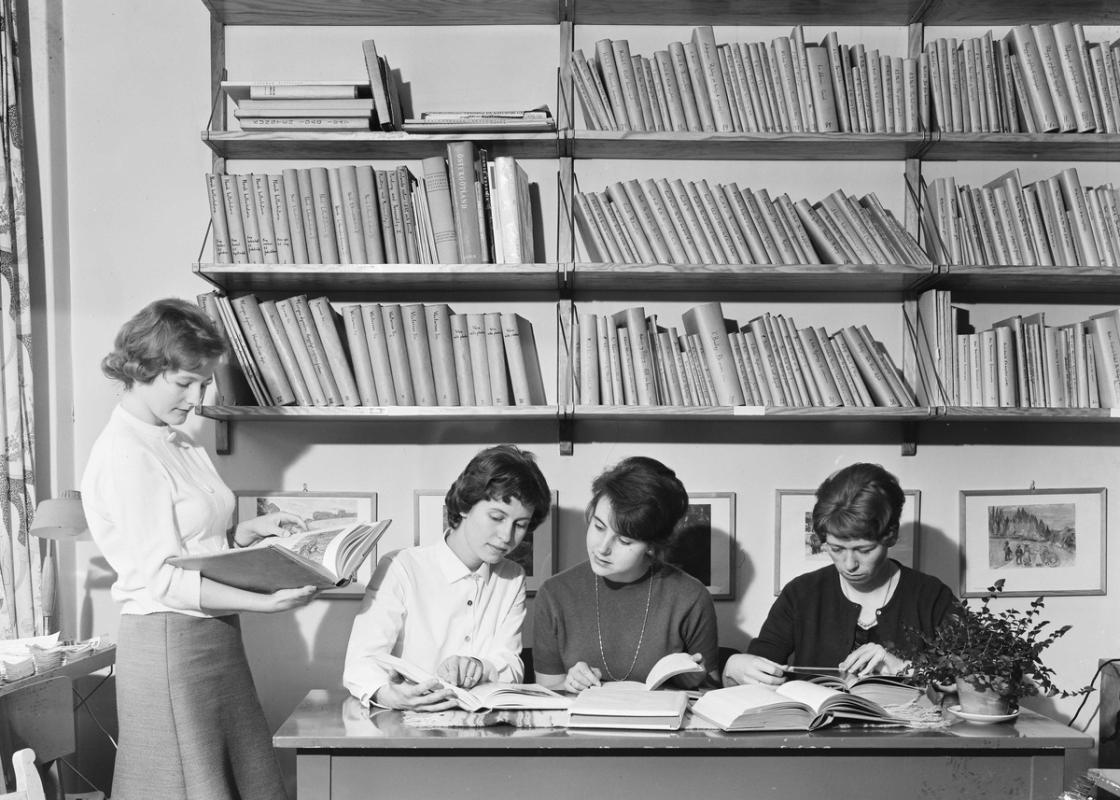

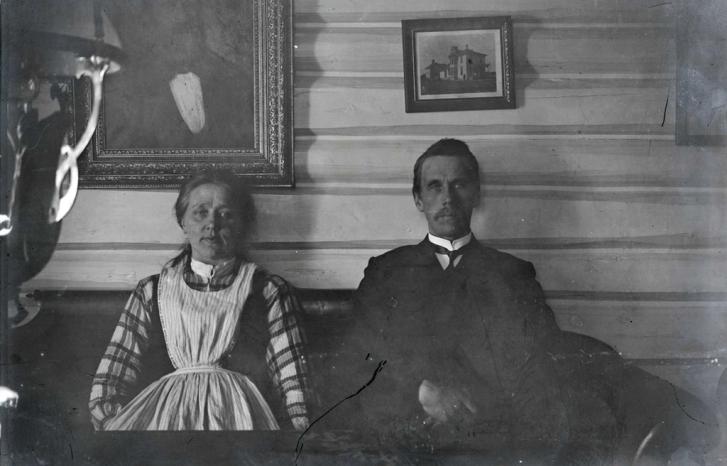

In 1882, women gained access to Norwegian universities, and, among other things, the centennial anniversary in 1982 was celebrated with important documentation work the exhibition The Daughters of Alma Mater – Women in the University 1882-1982. It was created by Astri Alnes, Vibeke Eeg-Henriksen, and Elin Strøm, and funded through various grants from several public authorities.

The exhibition gave an account of the few women who had gained access to the male dominated Kongelige Fredriks Universitet (The Royal Frederik’s University). The main focus was on the period before 1940, ending with the final question: Why are women still a minority among employees at the university?

The exhibition aroused massive interest and was shown at all Norwegian universities during 1982 and later at numerous other places. In 1988, the Centre for Women’s Research at the University of Oslo relaunched the exhibition in portable form, making it possible for others to have the exhibition on loan.

In 2005, the exhibition got its own webpage, created and administered by Kilden.

See exhibition: The daughter's of Alma Mater (only in Norwegian)

Norway left behind

During the 1980s, women’s research in Norway was institutionalised as various centres for women’s research at Norwegian universities and some university colleges.

These academic communities collaborated through e.g. the annual National Meeting of Gender Researchers. In 1992, the National Meeting agreed upon a more offensive strategy in order to realise the old dream of a women’s archive and an information and documentation centre.

The background to this initiative was the report Resources for providing information and documentation in the field of equal treatment for men and women in the European Community (Kramer and Larsen 1992) amongst other things. In this report, the situation in various European countries was documented and the establishment of a European network for national documentation centres for women’s research was proposed as well as a European women’s database.

The need for the establishment of documentation centres in counties without such a service was also called for. The European report brought the attention to Norway’s outdated position in this field.

“Be realistic, demand the impossible!”

Fride Eeg-Henriksen, the Head of Administration at the Centre for Women’s Research at the University of Oslo (present Centre for Gender Research) addressed the issue at the conference Viten, vilje, vilkår: Forskningspolitisk konferanse om kvinneforskning (Knowledge, Will, Conditions: Research Political Conference on Women’s Research) in 1992.

She maintained that scientific libraries is a necessary infrastructure for any research, and illustrated how other European countries had worked for the establishment of documentation and information centres for women’s research such as KVINFO in Copenhagen, Women’s History Collections in Gothenburg and so on.

“Be realistic, demand the impossible!” Eeg-Henriksen said, and applied to the Ministry of Church and Education for a 60 million Norwegian kroner heavy investment for women’s research. She proposed a “national institution for information, documentation, registration, and filing combined with local commitment from the university libraries.” (Eeg-Henriksen 1993).

With its modest fifty per cent librarian position and manual card index at the Documentation Service for Literature on Women at the University Library in Bergen, Norway lagged behind in this area of women’s research. The Documentation Service’ card index of women's literature was terminated in 1989 due to a new, electronic registration system.

In 1994, Fride Eeg-Henriksen and Gro Statle at the University Library participated at the second international conference for women working with information on women - Women, Information and the Future: Collecting and Sharing Resources World-Wide. The conference gathered approximately 300 librarians, documentalists, and information workers from all over the world.

One of the themes addressed at the conference was the construction of lists of keywords for women’s literature, since this was neglected by categorisation systems such as Dewey. Other issues that were up for discussion were information politics, institution building, and strategies for the development of collections.

Eeg-Henriksen and Statle maintained that Norway was not only lagging behind because we didn’t have our own documentation service. As long as we lacked our own documentation service, Norwegian women’s research would largely fail to participate in the international collaboration between the more than 100 existing documentation services (Eeg-Henriksen 1994, Statle 1994).

More reports, repeated propositions

Fride Eeg-Henriksen expressed herself clearly: Nobody does anything in order to establish a Norwegian women’s research database, nobody offers any online search assistance in international women’s research databases, and nobody is establishing a user’s service or ensuring the accessibility of women’s research literature.

Eeg-Henriksen asked for four librarian positions for what she envisaged as NORKVINFO, four research librarian positions at the university libraries, and funding for one position within expert communication to replace NRK’s outdated women’s archive and the like.

She also called for a central survey of academic events within women’s research in Norway and internationally, and an archive of the feminist movement, a photo archive of Norwegian women, and a women’s museum.

Centre for Women’s Research at the University of Oslo and the Secretariat for Women and Research at the Research Council of Norway collaborated for the funding of a new report on a Norwegian information and documentation service.

Fride Eeg-Henriksen and Torill Steinfeld, Head of Research at the Secretariat for Women and Research at the time, were the prime movers. The report “Information and Documentation Service on and for Norwegian Women’s Research” (Informasjons- og dokumentasjonstjeneste om og for norsk kvinneforskning) by Mie Berg Simonsen, maintained the following:

“In general, information systems within academia are characterised by traditional subject classifications and by the terminology of the traditional disciplines. At the same time, interdisciplinary fields such as women’s research are growing, but without satisfactory foundation and influence on these information systems. (…).

In Norway, systems for research information of various kinds are under construction, and it is therefore vital to establish an institution with professional competence and responsibility for documentation and information in the field of women’s research. This will not only contribute to the establishment of information systems as suitable tools for Norwegian research and its users; such a competence and resource centre will also form a significant link to international research” (Simonsen 1994).

The report proposed a network based service with a central unit in Oslo, and eight positions. At least four of these were meant for employees with information technological and library and archival expertise at the unit in Oslo, and the remaining four positions were to be located in the other University cities.

The Research Council grants support

Finally, their arguments came through. The Research Council of Norway decided to support the work with the establishment of a national information and documentation service for women’s research.

The majority of the Storting (the parliament) also voted in favour of the establishment of a “network based documentation and information service for women’s research in Norway”.

In 1995, advisors Elin Svenneby and Elisabeth Gulbrandsen at the Secretariat for Women and Research enthusiastically followed up the work with the establishment of the centre.

The new institution was called KILDEN, an acronym for “Kvinne- og kjønnsforskningens InformasjonsLinje og Dokumentasjonsenhet i Norge” (“Information Line and Documentation Unit for Women’s and Gender Research in Norway”).

In the work sheet “On the establishment of an information and documentation service for women’s and gender research in Norway” (Om etablering av en informasjons- og dokumentasjonstjeneste for kvinne- og kjønnsforskning i Norge) it was emphasised that the service was not meant to duplicate any activity that was already up and running. Instead, it was meant to provide the users of women’s and gender research with easy access to various types of information and documentation such as literature, books and journals, projects, overviews of existing competence, archives, overview of institutions, overviews of arrangements and events, photo archives and news archives.

Svenneby and Guldbrandsen suggested a location that would ensure the best possible contact with collaboration partners at other institutions. They recommended a foundation within a research community, but that the service be oriented towards the general public with enough funding for broad outreach.

A new report saw the light of day in 1995. This was about KILDEN’s relation to the libraries, written by Siv Wold-Karlsen. But the most significant happening this year was the clarification of KILDEN’s funding: The Research Council of Norway granted 700 000 Norwegian kroner to the establishment of KILDEN.

Turbulent times

The 1990s saw some major reorganisations within the public sector. In 1993, the various research councils were reorganised into one – the Research Council of Norway.

This resulted in uncertainty and internal discussion within the women’s research communities concerning the location and role of the Secretariat for Women and Research. At the same time, the public equality apparatus was reorganised and a Competence Centre for Equality was initiated (White Paper no. 70 1991-92 and Official Norwegian Report 1995:15, Halsaa 1997).

In this situation, which was turbulent for both research and equality politics, cabinet minister at the time Grete Berget proposed a merger of the planned Competence Centre and the Secretariat for Women and Research. The ministry appointed a committee in which the women’s research communities were represented to assess “possible benefits in a merger.”

The committee recommended a merger of the two institutions into a new Competence Centre for Equality and Women’s Research (Kompetansesenter for likestilling og kvinneforskning – KLOK) (Working team 1996). It also recommended that KILDEN be located with the Competence Centre.

The executive board at the Research Council was also in favour of this solution. Additionally, they wanted the research communities to be responsible for what is now the Journal of Gender Research (Tidsskrift for kjønnsforskning).

The women’s research communities were strongly against the KLOK recommendation. They claimed that a merger of the Secretariat for Women and Research and the Equality Council into a new Competence Centre would “lack legitimacy, confidence, and competence in the research community” (Proposition to the Odelsting no. 51 1996-97).

They were less concerned about the location of KILDEN, as the question seemed to drown in the debate concerning the Secretariat. At the end of the day, the Government gave way for the “strong resistance within central women’s research communities” on the merger issue while it still maintained its position regarding the physical location of KILDEN (Proposition to the Odelsting no. 51).

KILDEN was to be located with the governmental equality institutions instead of in the proximity of the research communities.

KILDEN sees the light of day

In the Research Council, they continued their work to give shape and content to KILDEN, and not least to work towards a clarification of its relation to the Secretariat for Women and Research.

Before too long the responsibility for the information and dissemination work, including the Journal of Gender Research, was transferred from the Secretariat for Women and Research to KILDEN.

KILDEN was given three positions. Two of these originally belonged to the Secretariat for Women and Research and were transferred to KILDEN. The third position had been vacant for a while, awaiting the start-up of KILDEN.

KILDEN was formally established by the Research Council of Norway on 1 September 1998, with Nina Kristiansen as its first director.

The women’s research communities were asked to suggest names for a project group. This group consisted of Beatrice Halsaa, Janneke van der Ros, Liv Byrkjeflot, Turid Markussen, Kari Sandø, Sigvor Kvale and Hanne Johansen. The leader of the group was Halsaa.

In 1999, KILDEN was organised as an independent information centre, affiliated to and mainly financed by the Research Council of Norway. The project group was appointed KILDEN’s first board, and on 2 March 1999, KILDEN’s website was launched with news magazine, resource database, the Journal of Gender Research and much more.

An English version of KILDEN was launched in 2007.

In 2015, KILDEN changed its name to Kilden kjønnsforskning.no.

About the author: Beatrice Halsaa is a political scientist and professor at the Centre for Gender Research at the University of Oslo.

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

List of references:

Working team: Om reorganisering av Likestillingsrådet, herunder en sammenslåing av Likestillingsrådets sekretariat og Sekretariat for kvinneforskning. Ministry of Children and Family Affairs. Oslo 1996

Berg, Mie: Litteratur og arkiver i kvinneforskning. NAVF’s Secretariat for Women and Research, Oslo, 1985

Colbiørnsen, Elisabeth: "Norge - et kvinnehistorisk u-land". Samtiden vol. 81 1972

Eeg-Henriksen, Fride: Kvinneforskningens framtid. Innspill om ressurser og organisering. Viten-Vilje-Vilkår. Forskningspolitisk konferanse om kvinneforskning. Work sheet no. 3, NFR/ Secretariat for Women and Research Oslo 1993

Eeg-Henriksen, Fride: "Informasjons- og dokumentasjonstjeneste om og for norsk kvinneforskning". Bulletine (2)6-6, 1994

Forskning om kvinner. En utredning om muligheter og behov for samfunnsvitenskapelig forskning om kvinners livsforhold og stilling i samfunnet. Committee appointed by the Council for Social Sciences Research in NAVF. The Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities and Universitetsforlaget (The University Press), Oslo, 1976

Gornitzka, Nina and Ravndal, Edle: Samfunnsforskning om kvinner. NAVF’s Secretariat for Women and Research, NAVF Oslo 1977

Hagemann, Gro: Kvinnehistoriske arkiver. Norwegian Private Archive Institute, Oslo, 1978

Halsaa, Beatrice: "Operasjonen var vellykket - men pasienten …..?" Bulletine (2)23-23, 1997

Recommendations from a committee appointed by NAVF’s Secretariat for Women and Research: Library and Archive Services for Scientific Women’s Material, NAVF, Oslo 1982

Johnsen, Inger: "Dokumentasjonstjeneste for kvinnehistorisk litteratur". Bok og bibliotek (1)86-87, 1975

Johnsen, Inger: "Dokumentasjonstjeneste for kvinnelitteratur". Synopsis vol. 8 no. 5 1977

Johnsen, Inger: "Kvinnedokumentasjon". Nytt om kvinneforskning no. 2 1983

Kvinneaspekter i humanistisk kvinneforskning. En konferanserapport. Oslo. The Council for Research in the Humanities, NAVF The Norwegian Research Council for Science and the Humanities, 1976

Kramer, Marieke and Larsen, Jytte: Resources for providing information and documentation in the field of equal treatment for men and women in the European Community. KVINFO, Copenhagen, 1992

Larsen, Jytte and Wedborn, Helena: "Nordic women’s documentation centres". NORA Nordic Journal of Women’s Studies vol. 2 no. 1 1993

The Equality Committee: Recommendations no. 1. The University of Bergen, Bergen, 1973

Official Norwegian Report no. 15 1995: An Apparatus for Equality

Samfunnsforskning om kvinner. Arbeidsnotat. Report no. 1. NAVF’s Secretariat for Women and Research, NAVF, Oslo, 1977

Simonsen, Mie Berg: Informasjons- og dokumentasjonstjeneste om og for norsk kvinneforskning. Sekretariatet for kvinneforskning, Research Council of Norway, Oslo, 1994

Skjønsberg, Kari: "Arkiv og dokumentasjon for kvinneforskning". Synopsis no. 15 1984

Statle, Gro: Refleksjoner fra Konferanse om dokumentasjonssentre for kvinner. Bulletine (2)7-7, 1994

White Paper no. 70 1991-92: On Equality Politics for the 90s

Strømberg, Erling: The Role of Women's Organizations in Norway. Oslo: Equal Status Council, 1984