Thalidomide was supposed to cure morning sickness in pregnant women. However, its side effects were stillbirths and around 100,000 babies being born with unusually short arms and legs. The drug was withdrawn from the market in 1961, having been sold in over 50 countries.

The Thalidomide scandal is one of the reasons why there is still less research on women’s health than on men’s. After the impact of Thalidomide on pregnant women became apparent, experimental drugs were only tested on men for many decades. In 1977, the US Food and Drug Administration banned testing on women of childbearing age.

When drugs are developed, they are thus not adapted to the female body and have different side effects for women than for men.

“As a consequence, the harmful effects of drugs on women have probably been overlooked, and effective drugs for women have probably been rejected, because they have only been tested on men.”

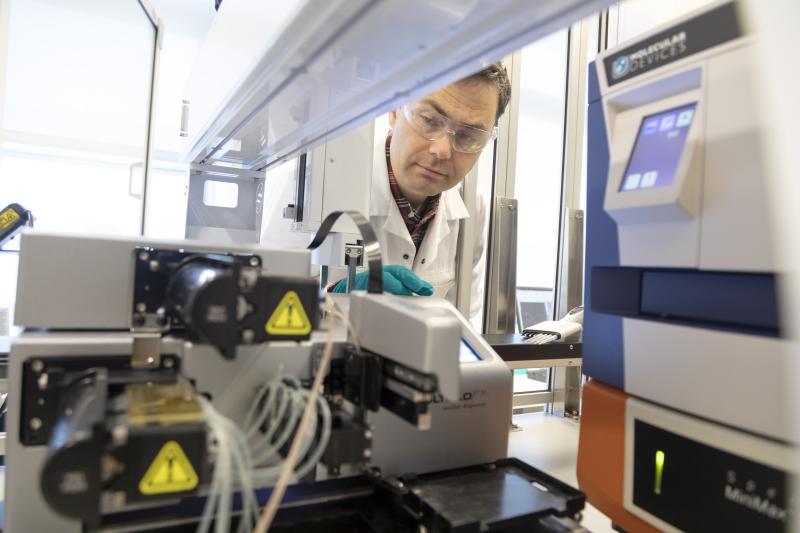

This is according to Torkild Visnes, a SINTEF researcher working on biotechnology and nanomedicine.

Drug doses are also adapted to a male body weight, which is normally heavier.

Gender is not defined by the bikini line

The drugs that are developed today are still primarily adapted to the male body. Drug development commonly starts with laboratory trials, where chemicals and drugs are tested under controlled conditions, before going on to animal trials, and finally clinical trials on humans.

“All cells and all organs have a gender. There are thus gender differences throughout the body and not just in the reproductive organs or, to put it more simply, under a woman’s bikini,” says Helga Bergljot Midtbø.

Midtbø is a cardiologist and associate professor at the Centre for Research on Heart Disease in Women at the University of Bergen. She refers to the widespread notion that women’s health is primarily about the breasts and the genitals, pointing out that it is also about how diseases that affect both women and men affect them differently. Take heart disease for example.

Possible effects relating to gender are deliberately being overlooked.

Since cells also have a gender, the gender imbalance in health research starts at the cellular level. The gender of the cells used in laboratory trials are rarely specified. They have been grown in the laboratory on animal blood components with unknown hormone levels, says Torkild Visnes. Hormone-disrupting substances are used in cultivating the cells.

“Almost everything we know about basic cellular biology has been done under the same conditions. We don’t know what blind spots this has created in our knowledge.”

When the drugs are then tested on animals, it is common to use only one gender – generally male animals.

But animal testing is unpopular, and the number of animals used in these trials should be reduced. Reducing variation also enables fewer animals to be used in testing,” he explains. The researchers prefer to do research on male animals because they do not have a menstrual cycle, which means their hormone levels are more stable.

As a consequence, there are few studies investigating the differences caused by hormone levels, cycle, age and circadian rhythm.

“Possible effects relating to gender are deliberately being overlooked. It’s fascinating.”

Men clearly benefit from a gender perspective

If a drug has made it to the clinical trial stage, it is an express goal that both men and women should be represented in the trials. However, women are underrepresented here too. There are several reasons for this, according to Midtbø.

“Women are older than men when they get heart disease, or they may have several coinciding diseases.”

This could mean that they do not meet the criteria, and are therefore excluded from the trial.

There has nonetheless been an ‘incredible decline’ in heart disease in Norway, she says, thanks to prevention efforts and mapping risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure and cholesterol. These also differ for women and men, and this is an area where there is some potential for improvement, according to the researcher.

“We are not very good at taking gender-specific risk factors into account, such as a previous record of pre-eclampsia, migraine or erectile dysfunction,” says Midtbø.

Both Visnes and Midtbø believe that a gender perspective in health research does not only benefit women.

“It will obviously benefit women, but men will benefit too,” Visnes points out.

“There are gender differences in the dosage of many common heart drugs. Conducting separate analyses of men and women will make it easier to determine the right dose in the future,” says Midtbø.

She points out that although there is less research on women's health, there is no benefit to being a man with heart disease: Men suffer from heart disease earlier and more often.

There are ethical limitations on what we can research, we are restricted by the technology, we can’t measure everything.”

Personalised medicine

Norway’s first national strategy for personalised medicine was published in 2014. But what exactly is it?

“Personalised medicine employs a lot of genetic testing. If you have a specific gene variant, you can get a personalised drug. What we don’t know much about is how drugs are affected by and interact with sex hormones. That could be important, because they affect the cells at a fairly basic level.”

“Why don’t we know more about how sex hormones and drugs interact?

“We don’t know more about it because it’s a question scientists have never asked themselves.”

We also want others to reproduce the research – which is easier when you can start with what we can call a ‘standardised human’, i.e. a common, homogenous, typical human. However, there are many variations to consider in addition to gender. For example, age."

For the sake of comparison, Visnes uses the analogy of a drunk man (or woman) who has lost their keys in the dark. They look under the streetlights. Not because they are most likely to be there, but because it is the only place they have a chance of finding them.

“This is what research is like too. We have to search under the streetlights. There are ethical limitations on what we can research, we are restricted by the technology, we can’t measure everything.”

Visnes believes that researchers may also be limited by the conventions of their field and subjective perceptions of reality.

“That is why it's so important to work actively to incorporate a gender perspective into our research.”

Sex hormones and how they affect the way people respond to drugs has not been systematically looked into before, he explains.

Furthermore, if we are to start looking at how different samples react in cells, which are both ‘male’ and ‘female’, a lot more samples are needed, according to Visnes. This will be difficult for most laboratories.

He is optimistic nonetheless: technological advances will make it possible to do more and more testing.

A new women’s health strategy

The Government launched its women's health strategy on 3 October. One of its goals is to increase knowledge about women's health, including incorporating the gender perspective in research. The strategy builds on the Women’s Health Committee's 2023 report.

The report points out that the committees tasked with assessing and approving ethical research rarely request a gender perspective. In the strategy, the Ministry of Health and Care Services supports the Women’s Health Committee’s criticism. Torkild Visnes believes a call for the National Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (NEM) to require gender-specific analyses from researchers will help address this. This is something the Norwegian Food Safety Authority, for example, can address in relation to animal testing, he says.

However, it is not that simple in practice.

“The number of individuals tested on will have to increase to generate statistically viable data. That, in turn, increases the cost of testing drugs, both in purely human terms, but also financially.”

It may not be enough to merely refer to guidelines, says Midtbø: funding will also be needed. She notes that the strategy includes a call for better use of health data, and that existing health registries must report gender-specific findings. This was a point the Centre for Research on Heart Disease in Women made to the Women's Health Committee.

“We have very good register data in Norway, and these registries represent many opportunities for research on gender that have not been fully exploited before,” she says.

Both researchers and politicians are becoming increasingly aware of the gender perspective. At the same time, Visnes believes that creating a health strategy for women has both advantages and disadvantages. For the sake of comparison, gender is only mentioned twice in the 2023 national strategy for personalised medicine.

“It is strange that women’s health is kept separate. It would be a better idea to have a gender perspective in the personalised medicine strategy, rather than making it a separate field. I don’t think the specialisation will benefit women’s health,” says Torkild Visnes.

“Could a health strategy dedicated to women make us forget about the male gender?"

“The women's health field has been fortunate to have important special interest organisations like the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association fighting its corner,” says Helga Midtbø.

“The Research Council has not held dedicated calls aimed at men's health issues in the same way as it has for women's health. Nor do we have a screening programme for cancers that only affect men, as we have for women.”

Gender research is not a competition between the genders, says Midtbø.

The Government launched its women's health strategy on the significance of gender for health on 3 October. The Government has set itself three goals:

- Good life-long women’s health

- Equal health and care services and equalisation of social health inequalities

- Higher quality through increased knowledge of women's health

In the national budget presented on 7 October, the strategy was followed up with an allocation of NOK 13 million. The Government also proposes that gender perspectives be included as part of the statistics for national health research and that special requirements should be set for incorporating gender as a variable for research in calls for funding from the Ministry of Health and Care Services.

Source: regjeringen.no.